|

| "Personal Effects of Unknown Man Shot at Grinnell June 30, 1914" Grinnell Historical Museum |

###

The events of June 30, 1914 quickly and unexpectedly splashed onto the pages of Grinnell's two newspapers. Although the shooting had occurred about 2:30 PM on Tuesday, the 30th, the Grinnell Herald, which published on Tuesdays and Fridays, managed to print a brief report on the murder in its June 30th edition. Short on specifics, this first newspaper account announced the main themes of the story: "Weak Minded" Frank Raleigh, who worked at the Monroe Hotel, had somehow concluded that a man sitting on a bench in the Grinnell depot's waiting room was involved in the "white slave trade," what today's newspapers call human trafficking. Raleigh drew

a revolver and shot and almost instantly killed a stranger...[who] ran out on the platform in front of the depot, where he dropped. He was taken into the office of the old Chapin House and died in a few minutes (Grinnell Herald June 30, 1914).

|

| Grinnell's Rock Island Train Depot (ca. 1900) Digital Grinnell |

The newspaper continued, pointing out that, before anyone could restrain him, Raleigh had fled "in a northeasterly direction." But then the newspaper turned attention to the victim, whose identity could not be established. "He was," the newspaper remarked, "a young man, of light complexion and wore a blue shirt, a dark suit and brown shoes. The pockets contained little of value" (ibid.). The remaining prose focused upon Raleigh, who was said to have been employed at odd jobs around the Monroe Hotel "a long time." Known "to break out suddenly in wild bursts of shouting," Raleigh had nevertheless been judged harmless. Now the "weak-minded" man had committed murder and run away.

|

| Photograph of the Monroe Hotel (ca. 1905) Digital Grinnell |

|

| Joseph Carter 1914 Cyclone |

|

| Marshalltown Evening Times-Republican July 1, 1914 |

###

After the victim fell on the train platform and was carried into Chapin House, a doctor was summoned, but Dr. E. F. Talbot (1873-1943) arrived too late to do any good, and the dead man was then taken a few blocks to J. W. Harpster's Furniture and Undertaking on Main Street.

|

| Early 1900s Photograph of J. W. Harpster's Furniture and Undertaking business, 905 Main Street Digital Grinnell |

|

| Scarlet and Black December 9, 1914 |

###

But what about the man's possessions, now part of the Museum's inventory? Do these items contribute anything to learning the identity of the victim? |

| Photograph of top of the Williams Shaving Stick Grinnell Historical Museum |

Nothing in the newspaper stories indicates where the stranger slept during the several days he was in Grinnell, and the man's pockets indicate that he was living rough. Not only was his wallet empty, but he was also carrying his shaving tools around with him, rather than leaving them in a suitcase (which he did not have) or in his hotel room (which he also did not have). The Williams shaving stick (small) he owned was popular and long advertised as the "traveler's favorite." If ordered by mail from the Connecticut manufacturer, the shaving stick cost twenty-five cents, but merchants often discounted the price to attract customers, so the dead man might have paid no more than a dime for it.

|

| Photograph of Single-blade Razor Grinnell Historical Museum |

The stranger also carried in his pockets a single-blade razor encased in a narrow, rectangular box whose cover announced the manufacturer as the J. R Torrey Company of Worcester, Massachusetts. Advertised as a "real man's razor," Torrey razors were quite popular until safety razors took over the market in the mid-twentieth century. Indeed, for many years Arbuckles' coffee offered Torrey razors as a premium to those who regularly bought their coffee, an indication, perhaps, of how popular Torrey razors were.

|

| Advertisement from Wilmington Morning Star July 17, 1914 |

However, the razor within the stranger's box was not a Torrey product; etched into the steel of the razor blade is the name of an English manufacturer, Joseph Rodgers, "cutlers to their majesties." Apparently the Grinnell murder victim had replaced the Torrey razor that had originally occupied the box with its English cousin. Neither razor, however, was unusual enough to help identify the dead man.

What about the rest? The broken comb bears no identifying marks, except for the fact that it is broken, indirectly confirming that the stranger was living on the edge. The pen knife, now rusted closed, was also damaged, missing pieces of the decorative cover. The cuff links likewise added little to the search for the dead man's identity. If today wearing shirts that demand cuff links is unusual, that was not true in 1914 when men's shirts frequently required at least modest cuff links. Nothing in the stranger's cuff links sets them apart from those most commonly used.

The dead man also wore a brass ring, but it carries no inscription. Without knowing on which finger the stranger wore the ring, we can only guess at its meaning. It might be that he thought, as some still do, that wearing brass can "amplify energy," "create balance in the body," and assist various metabolic reactions in the body. Worn on the index finger, a brass ring is said to "bring out the qualities of leadership, executive ability, ambition, and self-confidence"—or so some believe. Perhaps the ring, if worn on the left hand, indicated that the victim was married, but the coroner did not reveal from which finger he had taken the ring. Nor did word from an anxious spouse reach the Grinnell authorities.

|

| Photograph of Button Hook Grinnell Historical Museum |

The murder victim also carried a button hook, commonly used at the time to "thread" shoe buttons, and often given out free for advertising purposes. The button hook in the stranger's pocket advertised "Burke's Shoes 7123-25 So. Chicago Ave." Perhaps this device implies that the murder victim had once lived in Chicago, as he apparently admitted to Elva Sparks, one of the Grinnell girls to whom he spoke. But by 1914 the Chicago building which Burke's shoes had once occupied was available for rent, Burke's business having moved or failed sometime previously.

|

| Advertisement from Chicago Tribune April 5, 1914 |

One might expect a man to carry a watch, but why carry around an empty watch case, and what was apparently a woman's watch case at that? Had the man won it in a game of chance? Or had he been obliged to cede the works on a bet, and kept the ornate case because it had some sentimental or real value?

The most intriguing item in the dead man's possession was a pair of dice. Who travels with dice in their pockets? Do the dice indicate that the man was a gambler, eager to embark on games of chance whenever he could? If so, had he recently lost big-time, since he had no money? Or was he addicted to gambling, in the process having lost all his money? No evidence survives to answer those questions. The meager possessions of the dead man tell us only that he was without money, was apparently sleeping rough, and had some affection for games of chance.

###The most revealing testimony came from Elva (sometimes Alva) Sparks, another Grinnell teenager. She testified that on Monday evening, the night before the shooting, the man had approached her, taking a seat beside her on a Central Park bench. She claimed that the man asked her if she didn't want to leave Grinnell, but that she had told him "no." Tuesday afternoon the stranger approached her again, repeating his question. When Sparks declined his offer a second time, the man, she said, "pulled her back on the seat and told her that she had to leave Grinnell." She said that she had then agreed to go, merely as a way of getting away from him. She then ran into Frank Raleigh—where they met she did not say—who questioned her about the stranger and what he had said to Sparks. When he learned the details, Raleigh said that that "was all that he wanted to know," and told the girl to report her story to the city attorney, Harold Beyer. The shooting, she testified, occurred as she was returning from the attorney's office on 4th Avenue.

The Rock Island agent, A. E. Yates, testified next, telling the inquest that Raleigh had approached him at the ticket window that afternoon at around 2:20, asking him to telephone Beyer to say that a white slaver was in the depot. Apparently Yates, too, was familiar with the strange behaviors of Raleigh, and dismissed Raleigh's request, making no effort to telephone Beyer. When Raleigh returned to the window a few minutes later, again demanding that Yates summon Beyer, the ticket agent reluctantly complied. Shortly thereafter Raleigh approached the ticket window a third time, demanding that Beyer be summoned. Apparently Yates turned away, but reported that he soon heard the shot and saw the stranger and Raleigh leaving the depot.

On hearing this testimony, the coroner's jury determined that "this unknown man came to his death by a gunshot wound fired from a gun in the hand of Frank Raleigh; and we do further find that he came to his death feloniously and that a crime has been committed." But the person who committed the crime was never apprehended, and therefore never faced trial.

###

What, then, can we make of this story and the pitiful remainder of this unknown murder victim? On a surface level, the shooting constituted explosive news, bringing unexpected violence to the usually more pastoral rhythm of life in Grinnell. The original reporting preferred to center the story around the mental condition of the shooter, Frank Raleigh, and the record of his Grinnell sojourn offered corroboration to this interpretation.

As the Grinnell newspapers repeatedly observed, Frank Raleigh was disturbed. The Herald offered the most detailed account, alleging that Raleigh had even consulted

As the Grinnell newspapers repeatedly observed, Frank Raleigh was disturbed. The Herald offered the most detailed account, alleging that Raleigh had even consulted

eminent surgeons [who] had told him that the trouble was in the nerves at the base of the brain and that an operation might remedy it but that the operation was so delicate that there were about 99 chances in 100 that he would not survive. So he never ran the chance (Grinnell Herald July 3, 1914).

"In his rational moments," the newspaper allowed, Raleigh was a "hard and willing worker and he spent many leisure hours reading at Stewart Library." In summary, the Herald, like most of Grinnell, no doubt, thought him an "odd character," but harmless. The reactions of Joe Carter and A. E. Yates confirm this view; these men ignored Raleigh's demands for help, and did so without worrying about the consequences.

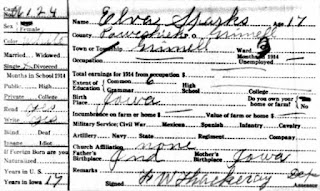

Other aspects of the story, however, make it less obvious that Raleigh was mentally unbalanced. For one thing, the fact that he escaped indicates that the man was capable of rationally analyzing his situation and pursuing a plan to avoid capture. Moreover, in retrospect Raleigh's concern about white slavery sounds more credible than it might have to Yates and Carter in the train depot. Particularly revealing in this respect was the testimony of Elva Sparks, the young woman whom the stranger tried to recruit, not once, but twice. At the time of her encounter with the stranger, Sparks was apparently 16 years old, although she later arranged for a delayed birth record that declared her to have been born April 15, 1896. During the 1915 Iowa census she told Frank Thackeray that she was 17 years old, which would mean that she was 16 when the events of 1914 unfolded.

Other aspects of the story, however, make it less obvious that Raleigh was mentally unbalanced. For one thing, the fact that he escaped indicates that the man was capable of rationally analyzing his situation and pursuing a plan to avoid capture. Moreover, in retrospect Raleigh's concern about white slavery sounds more credible than it might have to Yates and Carter in the train depot. Particularly revealing in this respect was the testimony of Elva Sparks, the young woman whom the stranger tried to recruit, not once, but twice. At the time of her encounter with the stranger, Sparks was apparently 16 years old, although she later arranged for a delayed birth record that declared her to have been born April 15, 1896. During the 1915 Iowa census she told Frank Thackeray that she was 17 years old, which would mean that she was 16 when the events of 1914 unfolded.

|

| 1915 Iowa Census card for Elva Sparks |

|

| Photograph of B.P.O.E. building on 4th and Main; the Antlers Hotel is visible on the right Digital Grinnell |

|

| Marshalltown Evening Times-Republican April 13, 1917 |

|

| Daily Gate-City (Keokuk) January 4, 1914 |

|

| Quad Cities Times January 11, 1914 |

In short, discussion of white slavery was frequent in 1914 Iowa, so it is not surprising that Raleigh had absorbed the main themes. In fact, as the Register proved, Grinnell townsfolk knew that Raleigh was preoccupied with white slavery.

He has been the butt of jokes and ridicule by those who took advantage of his unfortunate condition. Urged on by those who take delight in seeing him suffer, he has become obsessed with the idea that White Slavers were at work in Grinnell and that he was the one to thwart their plans...it evidently became a mania with him (Grinnell Register July 2, 1914).

###

So it was that a man whose mental health was known to be in question became preoccupied with one of the most prominent issues of 1914 criminal public law. How Frank Raleigh came to own a .38 automatic the record does not say, but we know that he brought that gun and his manic concerns about white slavery into the Grinnell train depot. There he fixed his attention upon a visitor to town, a man with no money, no identity documents, and a motley array of possessions. Persuaded that the man was a white slaver (and he may have been right), Raleigh shot and killed the stranger, and immediately fled, never again to be seen in Grinnell. The hapless victim was never identified, and so he was promptly buried in Hazelwood Cemetery's potter's field, leaving the meager contents of his pockets as witness to their unknown owner and the sad fate he met in Grinnell, June 30, 1914.