A recent study of childbirth in California revealed that Black mothers—even "rich" Black mothers—and their babies fare much worse in childbirth than do white mothers—even worse than poor white mothers. In this study 350 babies out of 100,000 children born to poor white mothers died before their first birthday, whereas 437 babies per 100,000 born to the richest Black mothers perished before their first birthday. The numbers are even worse for the poorest Black mothers, confirming that, although income powerfully affects the outcome of childbirth in the United States, race has an even more potent effect.

|

New York Times, February 12, 2023

|

Grinnell's small population and its even smaller population of African Americans make it difficult to see how this dynamic of childbirth played out in central Iowa. Of course, African American babies had been born in Grinnell almost from the very founding of the town. The great majority of all local births, however, had happened at home and had not automatically entered the record books. After the establishment of hospitals in Grinnell early in the twentieth century and the gradual transition of delivery to hospitals, record-keeping became more regular. But few Black children have been born here since then, making it difficult to know if in Grinnell there was any significant difference between African American births and all other births. |

Grinnell Herald-Register, December 29, 1955

|

I was thinking about this problem recently while skimming the December 29, 1955 issue of the Grinnell Herald-Register where I found a surprise: a photograph of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Thomas—both African Americans—holding their newborn twins, Anthony and Andrea, born December 26, 1955 at Grinnell's St. Francis hospital.

As I came to learn, both Anthony and Andrea (1955-2016) survived their first year, distinguishing themselves from the large numbers of Black babies in the California study who died before reaching their first birthday. But who were the Thomases? I had studied Grinnell's African Americans but I had never heard of Carl or Anna Mae Thomas. Today's post aims to recover the slimly-documented history of this Black American family that spent a half-dozen years in Grinnell in the 1950s.

###

Our story begins not in Grinnell, but rather in Monroe County, some sixty miles south of Grinnell. It was there in 1923 that Pearl Thomas (1882-1960), a 40-year-old African American man, took as his second wife 19-year-old Hazel Hollingsworth (1904-1973) (Albia Union-Republican, March 29, 1923). This union generated twelve children, one of whom, Carl Eugene, became father to the twins whose photo I discovered in the 1955 newspaper.

|

Albia Union Republican, March 29, 1923

|

Although Blacks were not uncommon in the early twentieth century in this part of Monroe County where coal-mining had given rise to communities like Buxton where Blacks were numerous, in Albia Pearl's family lived on the margins. Their home in the 500 block of B Avenue West quite literally placed them at Albia's geographic edge, a metaphor for their economic vulnerability. The precariousness of the family economy appears in Pearl's work history that shows him to have moved through a series of low-paying jobs. When Pearl first married in 1912, he worked as a "fireman" for a local firm ("Iowa, County Marriages, 1838-1934," FamilySearch); the 1920 US census remembers him as a "porter" in a bakery, and 1930 census described him as a "laborer" in an auto shop, a position that may explain how later that year Pearl advertised his business of washing and cleaning cars (Albia Union Republican, June 5, 1930).  |

Albia Union Republican, June 5, 1930

|

After the Depression settled onto Monroe County, Pearl cast about for work; by 1940 he was employed by the Works Progress Administration in road construction. The 1950 US census left blank the space where Pearl's work might have been listed, but evidently he organized a new business, hauling trash and garbage (see, for example, Albia Union Republican, December 29, 1955). Carl Eugene Thomas (1928-1995), who with his own family is the focus of our story, was the fourth child born to Hazel and Pearl. In 1940 Carl was still too young to be working, but when he registered for the military draft in 1946, Carl told the registrar that he was employed at a "malleable foundry" in Fairfield, Iowa. The 1950 US census has both Carl and his brother, Kenneth (1932-2014), "trucking fertilizer" for a feed store. Although the census does not identify Carl's employer, he likely worked for Goode Feed & Seed Co., an Albia business that sold fertilizer along with seed.

|

Lovilia Press, April 6, 1950

|

Soon after the census-takers left Albia, Carl married Anna Mae Brooks (1933- ) in nearby Pershing. Anna Mae was the child of Leonard Brooks (1903-1933) and Mary Tessel Washington (1910-1981). Leonard and Mary both had been born in Buxton, the mainly Black coal-mining town near Albia. Leonard's father had been a blacksmith (and minister), but from an early age Leonard had worked in the coal mines, an occupation that may have contributed to his early death (at age 30) from lobar pneumonia (Standard Certificate of Death, Monroe County, Rexfield Village, Registered No. 68-6). When Leonard married in Buxton in December 1928, he was 26 and his bride not yet 19 (Iowa State Board of Health, Return of Marriage to Clerk of District Court, 77-13647). At least one brother, William (1929- ) had preceded her into the family, but Anna Mae followed in May 1933, just a few months before Leonard's death in September. Consequently, Anna Mae grew up without knowing her father. Her mother remarried in December 1935, taking the Thomas's recently-widowed neighbor on Albia's B Avenue West, Lewis Dudley (1897-1961), as her second husband ("Iowa, County Marriages, 1838-1934," Family Search). The 1940 US Census shows Anna and her brother, William, living with their mom in the newly-blended Dudley family in Pershing, Iowa.

Carl was 22 in June 1950 when he married Brooks, who was then just 17. How the two met I do not know; Pershing is about 25 miles north of Albia, and in 1940 Anna would have attended elementary school there, and probably attended high school later in Knoxville. It seems likely, therefore, that the couple did not meet at school. However they got together, the match resulted in the birth of eight children. Their first child, Shelia Ann (1950-2013), was born September 1950 in the Albia home of Anna Mae's grandmother, Sallie (Harrelson) Brooks (1878-1952). In a telephone conversation with me (February 20, 2023), Anna remembered that at birth Shelia weighed more than 8 pounds and arrived in good health.

|

Undated Photograph of Anna Mae (Brooks) Thomas Juarez

(Facebook account of Anna Juarez)

|

Until the birth of Shelia Ann, the lives of Carl and his bride had centered on Monroe County, especially on Albia where the 1950 US census found about 4800 people. But at just this moment Carl and Anna Mae decided to take their little girl and move, first briefly to Des Moines, and then to Grinnell whose population the 1950 census counted at 6800. Because of this move, Carl and Anna were already resident in Grinnell when on February 3, 1952 Anna gave birth at Grinnell's St. Francis Hospital to her second child, Gregory Eugene (1952-1995), who weighed a healthy 8 pounds and 1/2 ounce (Grinnell Herald-Register, February 4, 1952). Anna's doctor for this and subsequent deliveries in Grinnell was Thomas Brobyn (1908-1966), who in post-war Grinnell practiced with Dr. Edwin Korfmacher (1904-1960); both physicians were on staff at St. Francis hospital. But it is Sister Pauline (1897-1991), who helped welcome generations of babies into the world at St. Francis hospital, whom Anna remembers now.

|

Sister Pauline with Dorothy Tarleton Palmer and Baby Cynthia (1949)

(https://digital.grinnell.edu/islandora/object/grinnell%3A12073)

|

One may imagine that it was the attraction of a job that brought Carl to Grinnell. Several of his siblings left Albia for Moline, Illinois and jobs at the John Deere Harvester Works, but Grinnell had no factory so large as that. If Carl continued the kind of work he had done in Albia, he might have driven a truck for one of Grinnell's two seed companies, DeKalb or Sumner Brothers. DeKalb was the bigger operation, and in Grinnell was headquartered in the former home of Grinnell Washing Machine Company at 733 Main (where today the Elks' Lodge stands). Sumner Brothers Seed Company's home at 4th and Spring was closer to the Thomas's first Grinnell home on Prairie Street (Polk's Grinnell City Directory 1940, p. 182).

|

Polk's Grinnell City Directory 1940 (Omaha: R. L. Polk & Co., 1940), p. 14

|

In fact, however, Carl worked at neither of these firms. Anna remembered that instead Carl worked for a Grinnell automobile dealer's service department. All these years later she could not recall the name of the dealership, but did remember that Carl often washed and polished newly-delivered automobiles, following in the footsteps of his father who had done similar work in Albia in the 1930s.

|

1932-1943 Sanborn Map of Western Grinnell

(https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4154gm.g026731943/?sp=8&st=single&r=-0.14,-0.025,1.281,0.59,0)

|

When Gregory, the family's second child, was born the Grinnell newspaper reported that the Thomases were living at 1003 Prairie Street, at the intersection of Prairie and Fifth Avenue, which at the time constituted the western-most edge of Grinnell (Grinnell Herald-Register, February 4, 1952). Although today a solid ranch house stands on that lot, nothing survives to describe the building in which the Thomases settled in 1952. When I spoke with Anna by telephone, she remembered the house as having had only one bedroom, and, like the Pearl Thomas home in Albia, the Thomas's first residence in Grinnell stood on what was then the outskirts of town.

Almost exactly one year after having delivered Gregory, Anna gave birth to the couple's third child, Leonard Macey; he, too, was born at St. Francis Hospital, weighing 7 pounds, 6 1/4 ounces (Grinnell Herald-Register, February 23, 1953). Telephone directories indicate (if the initial in the listing ["Thomas Carl W"] is an error) that by the time Leonard came home with his mother, the Thomases and their three children were living at 1031 Elm, a two-story house with three bedrooms, apparently a significant upgrade over the Prairie Street address.

|

1031 Elm Street (2013 photo)

|

The 1954 telephone directory found the Thomases at 714 Center Street, an address that brought them close to other African Americans. Carrie Redrick (1886-1969) was then living at 729 Center, just across the street a ways, and Eva Renfrow (1875-1962) was about two blocks away in the family home at 411 First Avenue. One may imagine, given the few Blacks then resident in Grinnell, that the proximity of African Americans brought Carl and Anna Thomas some satisfaction. However, Carrie and Eva, both widows and considerably older than Carl and Anna (Carrie was almost 70 and Eva was in her late 70s), may not have provided as much support as the Thomases hoped for. Moreover, the house on Center Street seems to have been much smaller than their Elm Street residence; a one-story structure, 714 Center could boast only two bedrooms and total living area of less than 1000 square feet.

|

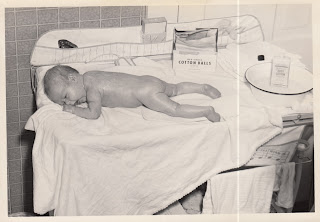

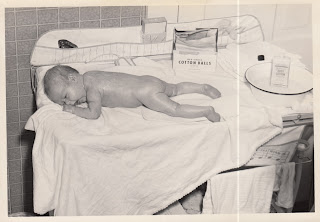

An Unidentified Newborn at St. Francis Hospital (1949)

(https://digital.grinnell.edu/islandora/object/grinnell%3A12074)

|

It was Anna's next delivery, again at St. Francis hospital, that brought into the world their twins, Anthony and Andrea. The newborns did not weigh quite as much as their older sister and brothers—Anthony weighed 7 pounds, 2 ounces and Andrea weighed 5 pounds 10 1/2 ounces (Grinnell Herald-Register, December 26, 1955)—but they were not seriously underweight, and both survived well beyond their first year. When Anna left the hospital, she brought the twins to their next Grinnell home at 723 Summer Street. At this point Carl and Anna had five children under the age of six, but their home had only two bedrooms and a living space of 636 square feet, less than either of their two previous homes.

|

723 Summer Street (2013 photo)

|

As with the house on Center Street, the Summer Street address brought the Thomases close to African Americans: another widow, Mamie Tibbs (1892-1973), at that time resided at 712 Elm which was just across the back yard from the Thomas home, and Mamie's second son, Albert Tibbs (1922-1997), and his family lived down the block from the Thomases at 707 Summer (since razed and replaced). Mamie, who would have been in her early 60s when the Thomases moved to Summer Street, was not in a position to help much, either financially or physically, as she had plenty of challenges to keep her own household operating ("The Hard Life of Widow Tibbs," in Daniel H. Kaiser, Grinnell Stories: African Americans of Early Grinnell [Grinnell: Grinnell Historical Museum, 2020], 157-166). Albert and Virginia Tibbs (1924-2014), on the other hand, although about ten years older than Carl and Anna, were closer in age and also had young children: If Albert, Jr. (1943- ), Larry (1944-2014), and Robert (Danny) Tibbs were older than the Thomas children, Barbara Tibbs (1948- ) was almost the same age as Shelia Thomas and a neighborhood playmate.

|

Albert S. Tibbs (1922-1997)

(Grinnell Herald-Register, March 3, 1955)

|

Like the Renfrow children of an earlier time, Shelia began school in Grinnell, the only African American in her class. I could not find a record to confirm my guess, but I assume that Shelia began school at Davis, entering kindergarten probably the same year her mother gave birth to the twins. If the Thomases left Grinnell in 1957, Shelia would then have also done first grade at Davis Elementary, which at that time served most of south Grinnell. She probably made her way to school in the company of her slightly older neighbor, Barbara Tibbs, who was almost certainly the only Black in her class, a grade or two ahead of Shelia. Before the Thomases moved to Wisconsin, Greg might have started school too, but I found no record to confirm that possibility.

|

Shelia, Greg, and Leonard Thomas, Grinnell Herald-Register, September 3, 1955

(Thanks to Monique Shore for taking this photograph from the library's bound copy of the newspaper)

|

On the telephone and again in a subsequent email, Anna made a point of the fact that her family had encountered no racial discrimination in Grinnell. Some support for that reading comes from a surprising source—a series of advertisements for the local dairy. Every ten days or two weeks Lang's Dairy published a photograph of young children, accompanied by an image of a Lang's milk carton and a ditty affirming the quality of the milk. Of the 100 or so Lang's ads I found in the pages of the Grinnell Herald-Register in the mid-1950s, only one advertisement included a photograph of Black children: Shelia, Greg, and Lennie Thomas (September 3, 1955). Of course, there were few non-white children in 1950s Grinnell so we can hardly be surprised that the children of only one Black family gained a place in the ads.

The details of the Thomas family's subsequent days in Grinnell remain unknown. Sometime before June 3, 1957, when Anna gave birth to Jeffrey C. Thomas—the couple's sixth child—, the Thomases left Grinnell for Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to live close to Anna's relatives. In addition to Jeffrey, in Milwaukee Anna delivered another two sons to the family—Steven in December 1959 and Ricardo Brooks Thomas (1962-2000) in 1962. All eight of the Thomas children, including the four born in Grinnell, successfully lived into adulthood, although four (including Andrea, the twin) died relatively early. Ricardo, the last-born, was only 37 when he died in 2000; Gregory, the first child born to the Thomases in Grinnell, was 43 when he died in 1995; Andrea, who struggled with both diabetes and asthma (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 7, 2005), was 61 at the time of her 2016 death; and Shelia, Anna's first-born, was just 62 when she died in 2013 (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 8, 2013).

|

Milwaukee Journal, January 28, 1995

(Thanks to Melissa Shriver of the Milwaukee Public Library who found and scanned this notice for me)

|

Carl, the focus of our story and father of the Thomas family, also died early; in January 1995 when still only 66 years of age, Carl died in Milwaukee and was buried in Graceland Cemetery there. At the time all eight of his children were still alive, but he and Anna had evidently parted ways: Carl's death notice makes no mention of Anna, but does remember his long-time companion, Evelyn Jean Davis. Anna remarried, taking as her second husband Roberto Juarez. A series of notes she posted in 2014 on the Findagrave websites of her deceased children indicates that she has retained a strong bond with her original family, including those children born to her in Grinnell, two of whom remain alive.

The New York Times periodically publishes biographies of people long gone but unnoticed at the time of their deaths. Entitled "Overlooked No More," the series tries to restore to the record obituaries of "remarkable people whose deaths...went unreported in the New York Times." With the little information presently available it is hard to argue that Carl Thomas or anyone else in that family was "remarkable," even for a small town in central Iowa. But plenty of Grinnell people had their ordinary lives regularly documented in the newspaper and in other records—from their church, their business, their club, their sports team, etc. The newspaper even found space to report on visitors or dinner guests. Not the Thomases, however; I could find no one who remembered them and the slim published record that survives does little more than confirm the presence in Grinnell of Carl and Anna Mae Thomas and their children. Born Black in Grinnell, these babies survived their infancy, like most other children born in Grinnell's hospitals in those years. All the rest disappears in the mist.