|

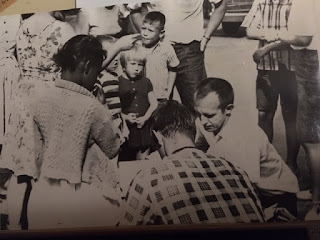

| Friendly Town guest Charlie Epting and host family member Brian Smith just after Charlie arrived in Grinnell, July 1966 (photo courtesy of Marcy Smith Keyser) |

|

| Daniel Rohr, 1963 St. Ansgar High School Yearbook |

Grinnell first participated in the "Friendly Town" program in 1965. With the help of local churches (especially the United Church of Christ-Congregational and St. John's Lutheran, which ran its own program), Grinnell families applied to host young, inner-city visitors for two weeks in July. This meant that at least briefly each summer very white Grinnell gained a small population of mostly black and brown kids who ate, slept, and socialized with their white host families. Today's post looks at Grinnell's experience with "Friendly Town," and how that history affected the understanding of race in central Iowa.

***

|

| Book jacket of Tobin Miller Shearer's Two Weeks Every Summer (Cornell University Press, 2017) |

Chicago's version of the Fresh Air program, dubbed Friendly Town, was launched in 1960, sending children to host families either in suburban Chicago or to families in more distant locations, such as North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana. The Iowa Friendly Town project, begun in 1965 largely through the efforts of Dan Rohr, saw about 250 Chicago youngsters visit Iowa that summer; the second year brought to Iowa some 500 Chicago children, who were joined by another hundred from Des Moines (Mason City Globe-Gazette, July 21, 1966). In 1969 some 300 children took part, all from Iowa (Des Moines Register, August 3, 1969). Restricting participation to Iowa children, organizers said, would allow better connections between host families and guests, now geographically close enough to encourage mutual visits after the Friendly Town experience (Des Moines Tribune, April 24, 1968).

***

Harry Reynolds (1903-1977) headed the initial effort, but later Ted Mueller, Mrs. C. Edwin Gilmour, Mrs. Tom Mattausch, Mrs. John Steger, and others took over administering the Grinnell visits. All the arrangements in Chicago—selecting the children; arranging for medical exams (!) in Chicago; coordinating transportation—passed through the Chicago Missionary Society. When the emphasis shifted to Iowa children, Des Moines volunteers organized the visits.

|

| Ted Mueller (right) helping organize the arrival of Friendly Town visitors to Grinnell, 1967 (photo courtesy of Berneil Mueller) |

To begin, Grinnell barely dipped its toe into the Friendly Town experience: in 1965, Grinnell's first year of participation, just three Grinnell families hosted three Chicago children, all from the same African American family. But in 1966 thirty-two Grinnell families hosted a total of thirty-four Chicago guests. Subsequently numbers of hosts and visiting children fell off: in 1967, when organizers admitted that they were having trouble recruiting hosts, twenty-one Grinnell families entertained twenty-three children; in 1968 twenty-two families volunteered, but with only sixteen children available, several families shared children, each hosting a child for one week. I could not find the names or numbers of hosts and guests for the next several years, as the newspaper seems to have lost interest in the project, perhaps a reflection of diminished interest among the hosts as well. If local records survive, we may learn more once the pandemic relents.

|

| St. John's Lutheran Church (undated photo) |

***

For the first couple of years of Iowa's Friendly Town, the Chicago visitors traveled by train, with the hosts paying $10 to help offset the expense. Once the Iowa program shifted its orientation to Iowa cities, Grinnell hosts paid only $5, and they met their guests by driving to the homes of the children they would host—mostly in Des Moines. In this way, organizers figured, inner-city parents would have a stake in the program, and rural hosts would gain insight into the families and homes from which their summer visitors came. |

| Chicago Friendly Town Visitors Disembark from the Train at the Grinnell Depot, July 15, 1967 (Grinnell Herald Register, July 17, 1967) |

|

| Jerry Anderson, Gerald Sykes, Chris Anderson, and Reginald Sykes (Grinnell Herald-Register, July 21, 1966) |

|

| Kim and LuGene Mueller with Virginia Torres (1967) (Photo courtesy of Berneil Mueller) |

|

| Ike Perkins riding a horse at the Maynard Raffety farm (Alan and John Kissane in front) (1966 photo courtesy Jim Kissane) |

|

| LuGene Mueller, Toni Keyes, Melanne and Kim Mueller (photo courtesy of Berneil Mueller) |

|

| Mark Langford, 1976 Des Moines Technical High School Yearbook |

|

| David Maggitt, 1969 Luther North High School Yearbook |

|

| Harry Ratliff, 1969 Luther North High School Yearbook |

|

| Gerald Sykes rides a horse on the Andy Tone farm (Grinnell Herald-Register, July 25, 1966) |

|

| Brian Smith and Charlie Epting showing the results of fishing at Grinnell Country Club pond (1966 photo courtesy of Marcy Smith Keyser) |

|

| Eugene and Darlene Smith, Martha, Marcy, Mindy, and Brian Smith with Charlie Epting (photo courtesy of Marcy Smith Keyser) |

it was just about having fun and just being around different people. This area [in Chicago where I lived] is just all black and I haven't been around white people or any other color. The schools I went to were all black; no Hispanics, no nothing. But [the white North Dakota hosts] treated me nice and once we got to know each other the color just left; there was no color; everything was OK (https://marillacfriendlytown.wordpress.com/oral-history).Perhaps most Grinnell hosts felt the same, hoping that their two-week experiment of domestic integration had brought their guests some fun, but had also improved race relations, even if only by a small amount. Kim Mueller, now a Chief United States District Judge in Sacramento but in the 1960s a child in the Ted and Berneil Mueller family, wrote me to say that she thought that Friendly Town had had a big impact on her, helping open her eyes to racial difference in a town that was overwhelmingly white (personal communication, August 27, 2020). It seems likely that other Grinnell kids also broadened their understanding of race, and appreciated the experience.

|

| 1987 photograph of the Ben Franklin store on Main Street (Digital Grinnell) |

What about the guests? Recently Toni Keyes wrote Berneil Mueller to say that Friendly Town visits had given her and her siblings (who visited in other Iowa communities) "a fresh outlook on people who looked different than us...We learned...that all people are basically the same..." (personal communication from Berneil Mueller, August 27, 2020). Charlie Epting, who had seen the world with the US Army after growing up in Chicago, remembered Grinnell very happily when recently I found him by telephone in Florida; he expressed his appreciation for the friendship that he and his mother had had with members of the Smith family. Perhaps many other Friendly Town visitors to Grinnell took away similar experiences, but my inability to find them or to coax replies out of those I did find makes it hard to know what the visitors absorbed from their experience in Grinnell.

Unfortunately, no one seems to have asked the kids about problems with their hosts, but it would not be surprising if some local hosts, most of whom had had little contact with persons of African American or Latino descent, had unthinkingly deployed in the presence of their guests some then-common, impolite epithets to describe African Americans or Hispanics. The kids themselves might have been even less careful, giving expression to racial stereotypes in the heat of play. Indeed, one Grinnell host family member recalled that a neighborhood boy had shouted the n-word at their Friendly Town African American guest, indicating that at least occasionally reminders of racial difference were mixed with the fun and farm animals.

***

Grinnell's experience with Friendly Town took place at a critical time for American race relations. If 1964 saw enactment of the U.S. Civil Rights Act and 1965 witnessed passage of the Voting Rights Act, these same years produced widespread unrest in American urban, black communities. While civil rights activists participated in sit-ins, freedom rides, and marches across the U.S. South, racial tension within northern American cities exploded several times, most notably in the 1965 race riots in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, and again in 1967 in Detroit and Newark. The following year brought the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had long argued for a peaceful resolution of racial and economic inequities. Meanwhile, third-party candidate George Wallace pursued the presidency on a blatantly segregationist platform.As a result of these and many other moments of racial strife, more radical agendas gained greater followings among the country's African Americans. The Nation of Islam, for instance, which had been founded decades before to advance racial separation, occupied an increasingly prominent place in the nation's consciousness, as hopes for peaceful integration waned. The Black Panthers, often depicted in the press fully armed, advanced a militant struggle against white American racial and economic dominance.

|

| Undated image of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, armed with Colt .45 and a shotgun at Oakland Black Panthers HQ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Panther_Party) |

Friendly Town does not lead to structural change. Black children are tolerated in white communities for two weeks, but the communities [themselves] remain unchanged...Nor does Friendly Town address itself to the institutional racism that produced and sustains black poverty (https://marillacfriendlytown.wordpress.com/).

|

| Sandra Bates (1968 Cyclone) |

Negro Americans are still strangers in their own house. More than 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation they are still exceptions to the melting pot theory... [M]ost white Americans are determined that [Negroes] shall not even get in the pot. To put it bluntly, the full privileges of citizens of the United States do not apply to Negroes—and they never have (Grinnell Herald Register, May 20, 1968).Within a few weeks of Bates's address, another group of inner-city kids arrived in Iowa to enjoy a brief "vacation" in Grinnell. No doubt most had fun, did things they had never done, and spent more time with white Americans than they ever had before. But for all its liberal ambition and good intentions, did Friendly Town prove, as Dan Rohr had hoped it would, that "under the skin all little boys and girls are pretty much alike?" Did the Friendly Town visits change Grinnell or help demolish institutional racism?

Members of Grinnell's host families offer contrasting views. Some visits seem to have gone off splendidly, host families maintaining contact with their visitors long after the Friendly Town visit ended. For example, the Robert Smith family traveled to Chicago to visit their former guest as well as their neighbor's Friendly Town guest who lived in Chicago's Robert Taylor Homes. Similarly, Darlene Smith exchanged correspondence with Charlie Epting's mother for years after Charlie's 1966 visit (thanks to Mindy Smith Heine for sharing with me copies of these letters). And Berneil Mueller recalls that her family became friends with Toni Keyes's Des Moines family, maintaining contact until the Keyes family moved out of state. In very white Grinnell, these on-going connections with African Americans certainly helped erode the sense of racial difference.

Other Grinnell hosts offered less encouraging recollections, reflected perhaps in the gradual demise of the program. One host told me that their family's guest spent most of his two weeks on a bicycle, away from their home and all on his own, interacting minimally with hosts. Hosts to the guest caught shop-lifting learned that their Chicago visitor had encouraged other kids to try it, thereby implicating them in the theft. The fact that the offender was white did nothing to undermine perceptions of difference. Still other Friendly Town hosts could find little to recall about this experiment in social relations; those two weeks long ago spent in the company of an inner-city child had simply disappeared from memory, and therefore could not have had much effect on local opinions on race and class.

|

| Undated photo of some of the Robert Taylor Homes on South State Street, Chicago (https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/robert-taylor-homes-chicago-illinois-1959-2005/) |

Even Dan Rohr, who, more than anyone, was responsible for bringing Friendly Town to Iowa, seems to have left it firmly in the past. When interviewed in 1966 after having seen two years of Friendly Town visits to Iowa, Rohr—who left college after his second year to help organize the program, and only completed his education some years later—thought that his Friendly Town work had been important, telling a newspaper reporter that "This [Friendly Town] and the past year in Chicago have changed my life considerably and I am sure it has been all for the good" (Mason City Globe Gazette, September 24, 1966).

Now living in California and retired from a career as a public-school teacher and an information technology specialist, Rohr seemed surprised when I found him by telephone and asked what he now thought about Friendly Town and his role in bringing it to Iowa. After a pause, he told me that these days he did not think about it at all; he had only a single folder of newspaper articles as a memento. He did not explain, but I wondered whether the enthusiasm with which he had originally embraced Friendly Town and its liberal vision of reform had succumbed to the enduring problems of racial conflict in America.