###

Beach Institute, founded in 1865, was one of many schools in the US South intended to educate African Americans who were prevented from public education by Jim Crow and southern racism. Several crises, including two serious fires, plagued the school which in 1914 had seven teachers for 168 students, the great majority of whom pursued "industrial" education (W. T. B. Williams, "Duplication of Schools for Negro Youth," Occasional Papers of John F. Slater Fund, no.15[1914],15).

|

AMA Staff at Beach Institute 1911-12

(List of Missionaries Under the Auspices of American Missionary Association 1911-1912 [NY: American Missionary Association, 1911], 10)

|

Meacham was not the first Grinnellian to serve at Beach: her fellow Grinnell alumna, Helen R. Field, had joined the staff at Beach immediately after her 1910 graduation (Grinnell Review 10/1910, p. 14), and no doubt provided helpful advice for the newcomer. Unfortunately, soon after Meacham arrived in Georgia, Field fell ill with "breakbone fever"—dengue fever—which probably limited the help she could provide the new recruit (GR 10/30/1912; GH 10/15/1912). As a slim diary for 1913 confirms, Meacham found teaching Beach high schoolers a challenge, but she worked hard, in the process having become a much-valued staff member. In her third year at Beach Meacham herself fell seriously ill and was obliged to return to Grinnell to recuperate. Instead of teaching at an AMA school the next year, Meacham taught at a Grinnell area rural school while she recovered her health (Marshalltown Evening Times-Republican 6/10/1915; Clarinda Journal 6/8/1916).With World War I as background, Meacham took up her second AMA post in 1916, this time at Brewer Normal School in Greenwood, South Carolina (Clarinda Journal 6/8/1916). Founded as a Negro boarding school in 1870 by the AMA, Brewer Institute, as it was originally known, "furnished the majority of the best educated of the colored race" (Greenwood Daily Journal 5/13/1897).

|

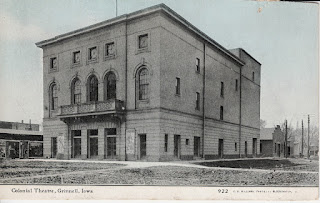

Brewer Normal Institute, College Building

(Greenwood Daily Journal 5/13/1897)

|

At Brewer as at Beach, most of the staff were women. Bessie Meacham was one of three who taught high school students; two taught elementary students, two taught "industrial" subjects, one taught music, and a Connecticut man was in charge of agriculture. Another unspecified illness interrupted Meacham's work in South Carolina, sending her back to Iowa in March 1918 to recuperate (Clarinda Journal 3/21/1918; Grinnell Review 4-5/1918, p. 332).

That autumn Meacham followed a somewhat different course in her work, perhaps because of the illness she had endured in South Carolina. Instead of heading south, she went west to Albuquerque, New Mexico where she spent a year at the Rio Grande Industrial School (Grinnell Review 12/1918, p. 34).

|

ca. 1909 Photograph of Heald Hall, Rio Grande Industrial School

(Rev. J. H. Heald, The Rio Grande Industrial School [Boston: Congregational Education Society, 1909]

|

Another AMA-sponsored institution, the Rio Grande school had a very different student body. Here, instead of African Americans, Meacham taught Mexicans in a school organized around practical education. Founded in 1908 on 160 acres that included stock and farm implements, the Rio Grande school began with twenty pupils and a curriculum dominated by agriculture. Most of the instruction took place in English, as part of the ambition of the school was to teach Mexicans English. However, since moral and religious ideas "are best imparted in one's native tongue," religious instruction came in Spanish (Heald, Rio Grande Industrial School, 5-7). As before at Beach Institute, Bessie Meacham was not the only Grinnellian on the Rio Grande faculty. In 1917 Mary Frisbie, a 1915 graduate of Grinnell, began teaching in Albuquerque and was still on the faculty when Meacham, returning to her earlier commitment to Black schools in the US South, left to take up a new appointment in Marion, Alabama (Grinnell Review 10/1917, p. 211; GH 8/23/1918; GH 8/26/1919).

Begun in 1867, Lincoln Normal prospered until the end of Reconstruction when local antipathy encouraged an arsonist to burn it down. Opposition within the state legislature resulted in a measure that prohibited the return of the institution to Marion, leading the AMA to abandon the project temporarily. Marion Blacks, however, had a different idea and, on the basis of their own subscriptions, raised money to reopen the school. This initiative persuaded the AMA to reconsider, sending teachers to Marion and purchasing a home for the principal. Although enthusiasm was high, resources remained skimpy, persuading the AMA in 1897 once again to withdraw from Marion. As before, however, Black families resisted, supplying funds to acquire some necessities and promising teachers that, if they remained at the school, parents of the school's students would feed them. Impressed by the commitment of Black parents in Marion, the AMA relented and resumed support. A burst of growth followed: by 1904 Lincoln Normal had 400 students (Robert G. Sherer, Black Education in Alabama, 1865-1901 [Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997], 131-33).

|

1922 Photo of Teachers at Lincoln Normal School; Meacham: first row, 3rd from left

(https://digitalcollections.libraries.ua.edu/digital/collection/p17336coll22/id/270/rec/1, Plate 35 )

|

Autumn 1919 Bessie Meacham left Grinnell for Marion, Alabama where for the next fifteen years she taught English and History at Lincoln Normal (GH 10/3/1919; Putnam Patriot 5/31/1934).  |

Undated Photograph of Students at Lincoln Normal School

(American Missionary Association Photographs, 1887-1952, Tulane University Digital Library: https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A3179) |

During her last several years at Lincoln Normal Meacham prepared herself to move from the classroom to the library. Every summer, beginning in 1930, she attended Chautauqua Library School in New York.

|

May 8, 1934 Letter of Bessie K. Meacham to LeMoyne College President Frank Sweeney (1929-40)

(Archives, Hollis F. Price Library, LeMoyne-Owen College; thanks to Jameka Townsend for sharing this document with me)

|

Consequently, when in 1934 she accepted a position in the library of all-Black LeMoyne (now LeMoyne-Owen) College in Memphis, Tennessee, Meacham had the equivalent of a master's degree in library science. Beginning as an assistant librarian, Meacham became head of the library in 1944 and remained in that position until she retired in 1952, having spent almost forty years working in Black schools in the U.S. South (Richland Clarion 7/31/1952).  |

Photograph of Bessie K. Meacham, Head Librarian, LeMoyne College

(1950 LeMoyne College Yearbook; thanks to Jameka Townsend for sharing this photo with me)

|

###

Although the places where Bessie Meacham worked in the years after her 1911 graduation from Grinnell demonstrate powerfully her commitment to changing the racist social order of twentieth-century America, it would be helpful to have her own words to help us understand what she felt about this work. Thanks to a 1912 Christmas gift from her sister, Floy, Bessie Meacham kept a diary for the calendar year 1913 and here she resolved to use the small booklet "to put down not only the facts and events, but [also] my thots [sic] on the same." Nevertheless, terse reports on the quotidian dominate the diary entries, only occasionally interrupted with insights into Meacham's life at Beach Institute.

|

Title Page of Bessie Meacham's 1913 Diary

(David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University, "Townsend Family Papers," Box 4)

|

As the diary confirms, Meacham saw all around her the hatred of white Americans toward Blacks. For example, the diary reports that in late January she visited a Black woman who had been enslaved to a white woman in whose household she now served as a free laborer. Her white mistress had not managed to accept the transition in the maid's situation, telling "her [that she would] kill her if [she were] not such a good worker." The white mistress went on to say that heaven did not appeal to her "if a nigger or Yankee goes" there too (January 30). Dr. Reid, a local white physician to whom Meacham went several times in 1913 for relief from illness, maintained that "the black man is only rarely capable of being a leader" (April 9). Not even the staff at Beach was immune to racism. According to Meacham's diary, the wife of the school's principal acknowledged that she "would rather have the white friend than a hundred colored" (March 17).

In addition to these real life experiences of racism, Meacham continued to be influenced by her reading, the choices of which seem to stem from her experience with the Social Gospel at Grinnell. Early in the 1913 diary, for example, she reported (January 2) that she was reading the latest issue of W. E. B. Du Bois's The Crisis. The December 1912 issue that Meacham read in early January in Georgia included a report on efforts of the Alabama legislature to "oppose any bill that would compel Negroes to educate their children... " (The Crisis, Dec. 1912, p. 61). A speech from Georgia's Senator Hoke Smith (1855-1931) quoted on the pages of The Crisis (ibid., p. 70) asserted that "The uneducated Negro is a good Negro; he is contented to occupy the natural status of his race, the position of inferiority...." A few pages earlier The Crisis informed readers about the arrest of a Black Georgia man who had "accidentally or intentionally touched a white woman with one of his hands." A hurried trial had found him guilty, the judge sentencing the defendant to twenty years in the penitentiary. After an appeals court granted the man a new trial, the same judge repeated the sentence, obliging the appeals court to reverse him again (p. 64). The journal also cataloged a series of the most recent lynchings and other murders of Black men (p. 65). With this literature in mind Meacham asked her diary (January 2), "Will nobody ever solve this 'eternal problem' of the black man's position in America?"  |

Undated Photo of Rev. Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918)

(https://abhsarchives.org/father-social-gospel-born/)

|

I suppose that Meacham learned of The Crisis from her Grinnell education, although I was unable to learn whether the college library had begun its subscription before Meacham's 1911 graduation. Other titles in her reading indicate Meacham's continued association with Grinnell College. Her diary several times reports that she was reading issues of the Scarlet and Black that her brother had sent from Grinnell. And when she returned to Grinnell in late May 1913 for summer vacation, she immersed herself in college happenings. May 30th, for instance, she attended Friday chapel to hear Dr. Steiner's brother speak, and the following day she and her brother, Frank, were present for the Hyde Prize orations.

On June 11th she took in her brother's college graduation ceremony at which Rev. Walter Rauschenbusch, a prominent advocate of the Social Gospel, addressed "The Call of Social Problems to the College Man and Woman." So far as the newspaper account can confirm (Grinnell Register 6/12/1913), Rauschenbusch did not mention race in his address. Nevertheless, elsewhere Rauschenbusch had argued that ...no man shares his life with God, whose religion does not flow out, naturally and without effort, into all relations of his life and reconstructs everything that it touches. Whoever uncouples the religious and the social life has not understood Jesus. Whoever sets any bounds for the reconstructive power of the religious life over the social relations and institutions of men, to that extent denies the faith of the Master (Christianity and the Social Crisis [New York: The Macmillan Co., 1907], 48-49).

Despite the absence of a direct reference to racial injustice, Bessie Meacham could hardly have wished for a more full-throated commendation of the career path she had chosen, helping reconstruct education and social relations for Black Americans in the U.S. South.

###

|

Photograph of 1966 Grinnell College Alumni Award Winners; Bessie Meacham front row, middle

(Alumni Scarlet and Black July-August 1966)

|

When contacted in spring 1966 by the college alumni office with news that she had been nominated for an alumni award, Bessie Meacham responded humbly: "I shall try to tell you of my life's work, although it may not sound very glamorous," she wrote. Summarizing her forty years at Black schools in the South, Meacham declined to characterize her "contribution to the education of the present generation of Negro youth," as the alumni office had evidently requested. "I have not been the kind of person who turns the world upside down," she concluded modestly (April 6, 1966 letter from Bessie K. Meacham to Mrs. Mullins, Alumni Award records, Grinnell College Office of Development and Alumni Relations).

The citation that accompanied her award at reunion in 1966, however, was more assertive, recognizing that Meacham had gone south "to help give negroes opportunity for education." "The benefits from her years of teaching," the citation continued, "are spread through many communities," including those at LeMoyne College with which Grinnell was then exchanging students ("Bessie K. Meacham, 1911," 1966 alumni citation, ibid.).

Neither George Herron nor Edward Steiner were around in 1966 to congratulate Meacham. But if they had been, these two giants of the Social Gospel would surely have praised her for taking her Christian faith deep into the heart of some of America's worst social ills. Her Christianity, although deeply pious, was also socially committed and intended to overturn the bias built into American racism.